Why Make Books?

For young children, books are magical, useful, and familiar. They are a classic circle time tool and are wonderful for explaining complex topics. Yet, for many museums no published books exist that explain their objects or their institutional values. Instead of relying on existing children’s books, the Smithsonian Early Enrichment Center (SEEC) has started creating our own books which act as scripted lesson plans with embedded images. These books can be easily applied to multiple programs.

Getting Started

To design our books, we use a presentation program. Best practice is to include one or two large photos and two lines of large font text per page. (There are several examples of pages from our books found in this blog.) If the object needs more context or explanation, it can be included in the author’s note. Books can be printed, laminated, and then collated in a ring binder for ease of use. A photo album service can also be used to create a more traditional looking book.

Interactive Stories

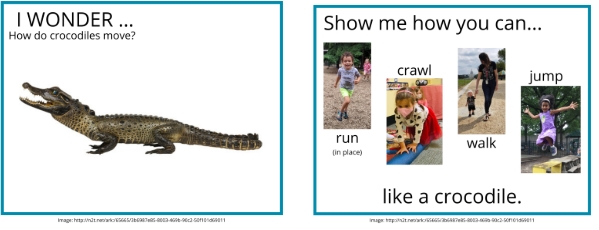

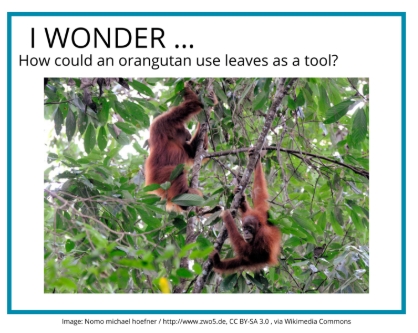

Interactive elements for your story times can be built into the books you create. The book can prompt you to encourage children to pretend, move, sing, and experiment. Writing activity breaks directly into the book allows children to have the opportunity to be active participants throughout the whole story time experience.

Questions & Wait Time

Core museum education practices such as asking questions and giving wait time can be written into books, too. We often ask a question on one page and make sure the answer is on the next page. Making the educator or docent turn the page is one way to intentionally slow down the reading of the story and allow for thoughts and conversations to develop.

Familiar / Unfamiliar

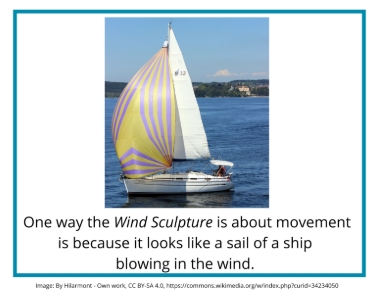

To start creating books, we identify and leverage subjects that are familiar to young children to create context for the unfamiliar. In writing our Wind book, we knew that most pre-k children have some familiarity with sailboats. They may play with boats in the bathtub or may have sailed on a real boat. Early in the book we made the connection that the Wind Sculpture was like a boat. This grounded the book in the familiar, and from there, we made additional connections to the unfamiliar.

Translating Complex Ideas

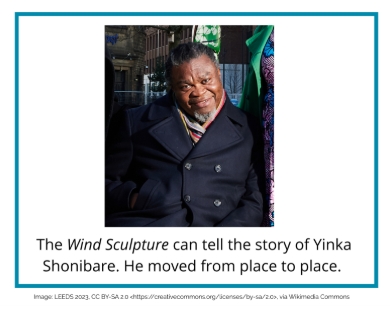

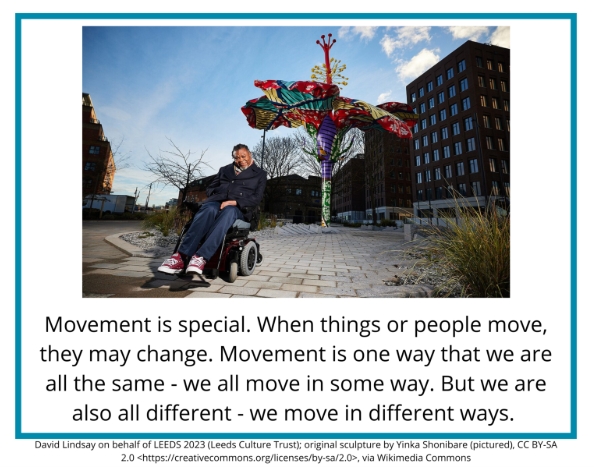

Our goal when creating books is to convey the true meaning of the objects to young children. Since source materials are not accessible to children, it is our responsibility to adapt them to make connections to the familiar. Artist Yinka Shonibare described the meaning of his piece as “None of us have isolated identities anymore, and that’s a factor of globalization” and we translated that quotation as:

Scripts & Key Phrases

Rooted in the philosophy of anti-bias education, SEEC uses the phrase, “We are all the same. We are all different.” This key phrase helps young children foster a positive sense of self while embracing diversity. Since this phrase is core to our hidden educational theories and values, we embed this script into our books. We encourage you to consider what values are core to your organization and how you can create a script that is relatable to young children and reflects those core values.

Longevity of Books

These books that we write can easily be pulled off a shelf and read. This makes them incredibly useful and easier to implement than a lesson plan. We love that they can be used over and over again by different classes and educators. Writing books may not be something that every preschool or museum educator does in their daily practice, but we encourage you to try, and you will likely have a product that you reach for again and again.

In the fall of 2015, the Friends of the National Zoo, National Museum of African American History and Culture, National Air and Space Museum, National Museum of American History, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Associates’ Discovery Theater, and the Smithsonian Early Enrichment Center, together with the DC Promise Neighborhood Initiative (DCPNI) were awarded a two-year grant through Grow Up Great, PNC’s initiative focused on early childhood education, to launch Word Expeditions. The grant’s objective is to build vocabulary in preschool students from the Kenilworth-Parkside neighborhood in Northeast DC. DCPNI works exclusively with this neighborhood supporting all members of the Kenilworth-Parkside and describes its mission as “improving the quality of their own lives and inspiring positive change in their neighborhood.” The group has a strong foothold with families of young children and so it seemed natural to integrate Word Expeditions into their already existing Take and Play structure. Once a month, Smithsonian representatives visit Neval Thomas Elementary School during which time, families participate in activities that teach about the Institution’s collections, build vocabulary, and support a child’s development. The evening concludes with a meal and families take home a kit from DCPNI outlining fun and simple ways to incorporate learning and vocabulary skills at home.

In the fall of 2015, the Friends of the National Zoo, National Museum of African American History and Culture, National Air and Space Museum, National Museum of American History, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Associates’ Discovery Theater, and the Smithsonian Early Enrichment Center, together with the DC Promise Neighborhood Initiative (DCPNI) were awarded a two-year grant through Grow Up Great, PNC’s initiative focused on early childhood education, to launch Word Expeditions. The grant’s objective is to build vocabulary in preschool students from the Kenilworth-Parkside neighborhood in Northeast DC. DCPNI works exclusively with this neighborhood supporting all members of the Kenilworth-Parkside and describes its mission as “improving the quality of their own lives and inspiring positive change in their neighborhood.” The group has a strong foothold with families of young children and so it seemed natural to integrate Word Expeditions into their already existing Take and Play structure. Once a month, Smithsonian representatives visit Neval Thomas Elementary School during which time, families participate in activities that teach about the Institution’s collections, build vocabulary, and support a child’s development. The evening concludes with a meal and families take home a kit from DCPNI outlining fun and simple ways to incorporate learning and vocabulary skills at home. A few weeks later, families are invited to come to the museum that co-hosted the

A few weeks later, families are invited to come to the museum that co-hosted the

accompanied by what I like to call, conversation starters. These conversation starters include key vocabulary terms that help families define some big ideas they can use to discuss the object. They also pose open-ended questions and suggest easy ways to engage with the object and use the vocabulary in ways that will help children understand and recall the word’s meaning. For example, The Smithsonian Gardens description asks families to look closely at an elm tree and find its parts. The children will walk away with a concrete understanding of terms like roots, trunk and bark. The National Portrait Gallery’s entry asks families to imagine what they would see, hear and taste if they jumped into the portrait of George Washington Carver and suggest that parents use the term five senses and, of course, portrait.

accompanied by what I like to call, conversation starters. These conversation starters include key vocabulary terms that help families define some big ideas they can use to discuss the object. They also pose open-ended questions and suggest easy ways to engage with the object and use the vocabulary in ways that will help children understand and recall the word’s meaning. For example, The Smithsonian Gardens description asks families to look closely at an elm tree and find its parts. The children will walk away with a concrete understanding of terms like roots, trunk and bark. The National Portrait Gallery’s entry asks families to imagine what they would see, hear and taste if they jumped into the portrait of George Washington Carver and suggest that parents use the term five senses and, of course, portrait. I find that dinner time at the Take and Play program provides the perfect opportunity for me to get to know families on a deeper level as I talk with them about the maps and their museum visits. Recently, I engaged in a conversation with two families who have become “regulars” at the workshops and museum visits. When I asked what museums the families had visited lately, the mothers immediately began to list all of the museum trips they had been on since the program’s inception in the fall and what’s more, they described their visits in detail – recalling the vocabulary that was introduced and the activities in which they participated. It was exciting to see their enthusiasm for the program and it was clear that the map had helped foster and grow their interest in museums.

I find that dinner time at the Take and Play program provides the perfect opportunity for me to get to know families on a deeper level as I talk with them about the maps and their museum visits. Recently, I engaged in a conversation with two families who have become “regulars” at the workshops and museum visits. When I asked what museums the families had visited lately, the mothers immediately began to list all of the museum trips they had been on since the program’s inception in the fall and what’s more, they described their visits in detail – recalling the vocabulary that was introduced and the activities in which they participated. It was exciting to see their enthusiasm for the program and it was clear that the map had helped foster and grow their interest in museums.

nses, a lot of other things can happen. They can use the experience to practice and build upon their vocabulary. Ask them questions: “What color is it?; How does it feel?; What does it smell like?. A parent can also enhance this experience by adding objects that can be used for comparison purposes. , Add parsley, for example, and encourage basic math skills by asking them to find shapes or compare the size of the two herbs. You can also stimulate critical thinking by adding elements like, scissors or water. These elements prompt children to conduct experiments: i.e. “What will happen if I cut the rosemary – will it still smell? or, What will the rosemary feel like when I pour water on it? Adding these components not only gets them to investigate and hypothesize, it also gives them the chance to practice their fine motor skills. Cutting and pouring are everyday tasks that they hope to master one day and using these skills will also aid in developing the coordination required for writing.

nses, a lot of other things can happen. They can use the experience to practice and build upon their vocabulary. Ask them questions: “What color is it?; How does it feel?; What does it smell like?. A parent can also enhance this experience by adding objects that can be used for comparison purposes. , Add parsley, for example, and encourage basic math skills by asking them to find shapes or compare the size of the two herbs. You can also stimulate critical thinking by adding elements like, scissors or water. These elements prompt children to conduct experiments: i.e. “What will happen if I cut the rosemary – will it still smell? or, What will the rosemary feel like when I pour water on it? Adding these components not only gets them to investigate and hypothesize, it also gives them the chance to practice their fine motor skills. Cutting and pouring are everyday tasks that they hope to master one day and using these skills will also aid in developing the coordination required for writing.

interaction during the museum visit. Often we ask parents to lead simple activities in the galleries that are open-ended and encourage observation and conversation. For example, we might ask infant/toddler parents to find all the boats in a gallery space or simply describe an object. If it seems odd to talk about having conversations with your little one, remember recent research is making direct correlations between how much a parent talks to their child and their literacy.

interaction during the museum visit. Often we ask parents to lead simple activities in the galleries that are open-ended and encourage observation and conversation. For example, we might ask infant/toddler parents to find all the boats in a gallery space or simply describe an object. If it seems odd to talk about having conversations with your little one, remember recent research is making direct correlations between how much a parent talks to their child and their literacy. Preschooler families might be asked to create a story or make a list of questions they have about an object. In both of these scenarios, we are encouraging independent thinking, literacy and providing time for you and your child to learn together. It is also giving the parent practice having open-ended conversations and ideas of how to use museums when there is not an educator around.

Preschooler families might be asked to create a story or make a list of questions they have about an object. In both of these scenarios, we are encouraging independent thinking, literacy and providing time for you and your child to learn together. It is also giving the parent practice having open-ended conversations and ideas of how to use museums when there is not an educator around.