Today we’re featuring Maya Alston and Amy Schoolcraft, the teachers of the three-year-old Wallaby class. The class has been busy exploring the Animal Kingdom, and I joined them for a lesson about amphibians and frogs at the National Museum of Natural History. Below you will find images from the lesson, as well as reflections from Maya.

For the past two years, a mallard duck has made SEEC’s playground her nesting ground to lay her eggs. Every year we section off a part of the playground for mama duck to lay her eggs safely and use this as an opportunity to engage the children about the importance of respecting her space while she cares for her babies. This was the Wallabies’ first time experiencing the process, and while they have always shown interest in animals through play, we noticed that this experience really seemed to stick with them and pique their interest. Amy and I decided this was the perfect time to begin a unit on the animal kingdom.

For their lesson, the class headed to Q?rius, an interactive learning space at the National Museum of Natural History, for their lesson.

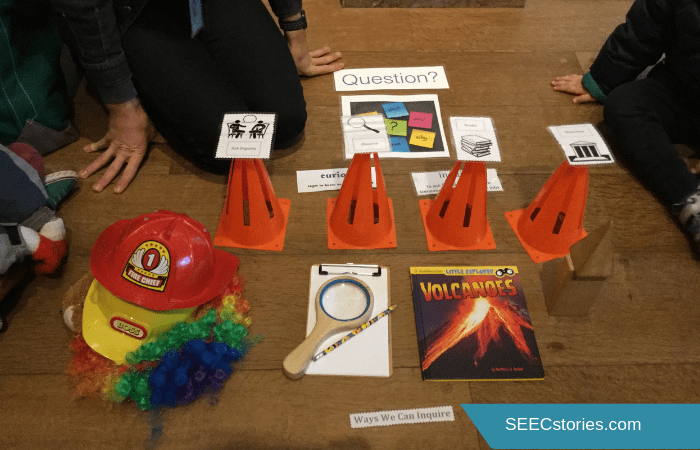

Q?rius is a space dedicated to encouraging young children to be curious and investigate through hands on exploration. I wanted my students to be active participants and be able to have tangible objects to help them make these connections. I took some time to explore Q?rius on my own first, imagining how my children could engage with objects that were relevant to our lesson. From there, I began to piece together what I wanted the lesson to look like based off what the space offered.

Since it was also my first time going to Q?rius, I wanted to make sure the space was appropriate for my students. I took time to explore on my own as well as speaking with Q?rius employees about what objects they had related to amphibians.

Q?rius has many objects and specimens to examine closely. Maya led the class to a case and took out a specimen box without showing the class. She gave the group some clues as to what might be in the box including making a frog noise with a frog musical instrument, and showing them an image of a frog. Between both clues many children exclaimed, “a froggie!”

For this unit, we wanted our students to understand the concept that animals belong to different groups. While animal kingdoms are generally taught in later years, I wanted to build a foundation of the concept of categorizing animals based on physical traits, habitat, and other characteristics unique to that animal group. In this lesson, we began exploring amphibians.

Maya shared two frog skeletons and allowed each child a turn to look closely. They noticed the difference in sizes between the skeletons.

Next, the class went upstairs to the Q?rius jr. space, a dedicated area of Q?rius for young children. They sat down and Maya told the class what they were going to learn about today: amphibians. They practiced saying the word and Maya explained that amphibian means two lives; one life in the water, and one on land. She asked what animals they know of that live in the water. The children listed animals such as sharks, fish, and dolphins. Next, she asked what animals live on land. They identified many animals including butterflies, cheetahs, birds, bunnies, and elephants.

Maya reiterated that amphibians are special because they live in both the water and on land, such as frogs. She showed them images of more amphibians including newts, salamanders, toads and caecilians. The group remembered some previously learned knowledge about how many legs insects have (six) and arachnids have (eight). Maya let the class know that many amphibians have four. The class counted the legs of the amphibians together. The group explored another physical aspect of amphibians – how they feel. The class felt their own skin and described it as smooth and soft. Maya let them know that amphibians are smooth and soft as well, but they’re also moist, meaning they’re always a little bit wet.

I knew very general information about amphibians and frogs, but to prepare for this lesson I took some time to research as well. Sometimes the children have questions that I might not have been expecting, so it’s always helpful to come with some additional information prepared.

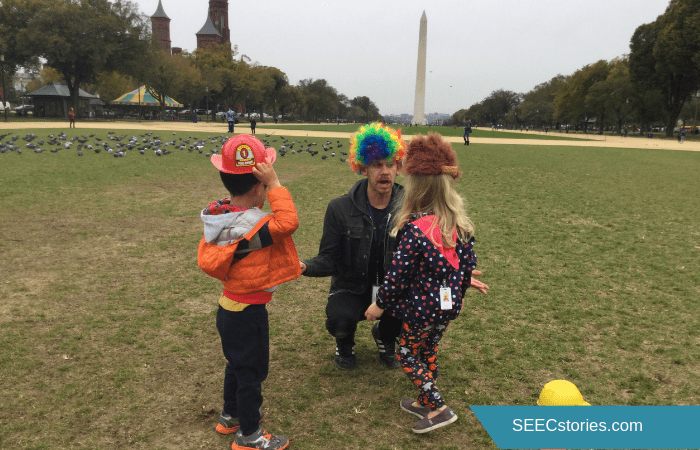

One of the children brought up how bunnies feel, and Maya took this opportunity to transition to her next point. She asked the group what bunnies like to do. They excitedly said, “hopping!” Maya told the group that frogs also like to hop. The class began jumping and hopping like frogs all over the circle. Maya let them have some time and then said, “3, 2, 1, and done.” The children took the cue and sat back down in their circle.

While I had not planned for the group to jump like frogs at this point, it was the children’s way of staying engaged and actively participating with the lesson. I really want them to connect with our lesson in a way that speaks to them, and most often, it is through movement. It makes our lessons feel a lot more organic and can even help to push the conversation along. I’ve found my lessons to be much more fun and exciting when I allow the kids to steer the direction we go in just a little during our discussions. It’s an excellent way to gauge their interest and see what they know already.

Next, they explored frogs more deeply by looking at plastic frogs, and playing wood frog guiro musical instruments. They enjoyed stroking the wooden frog’s back with the mallet and listening to the ribbit-like sound. They also compared the difference in sound between the larger frog guiro and the smaller one.

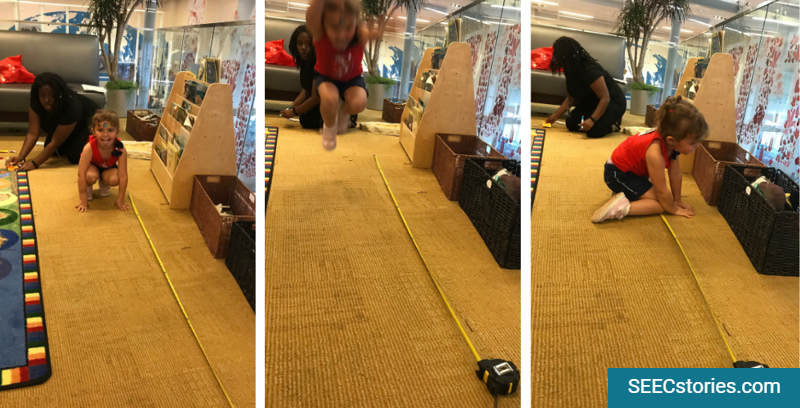

The last aspect of the lesson was to explore how strong frog legs are and how they help them to jump very far distances. Maya said that some frogs can jump up to seven feet! To illustrate this she measured out the distance with a tape measure.

The inclusion of math skills into the lesson was something that happened naturally. I really wanted to provide a visual to see just how far of a distance it was, and a tape measure was the perfect object. It just so happened to be a great way to incorporate math skills!

Then it was the children’s turn to jump like a frog and measure how far they could go. Maya randomly pulled each child’s photo from a bag to indicate it was their turn to jump.

The children seemed to really take to the activity portion and liked comparing their distances to see if they could jump as far as their friends. I think the activity was engaging enough that even when it wasn’t their turn to jump, they were still excited to get to participate in some fashion, for example cheering on their friend who was jumping.

There’s always a little bit of unknown when taking your students to a new space. Sometimes doing gross motor activities in confined spaces can be a little tricky. I wanted to make sure the kids were able to get the most out of the lesson, while also respecting other people using the space, so we discussed.

As each child jumped, the rest of the class cheered for them and how far they went. Maya integrated math skills by measuring how far each child went and writing down the numbers next to their photo. To conclude this part of the lesson Maya let them know that they were all great jumpers, but frogs could still jump a lot further and they would learn more about them later in the week.

I absolutely loved how the group waited so patiently to take their turn to jump and were cheering each other on. It can be difficult to wait patiently for eleven other people to go before it’s finally your turn. Unity and camaraderie are concepts we encourage throughout the year, and seeing them be so supportive unprompted was very heartwarming.

To end the visit, the class got a chance to explore the Q?rius jr. space. Some children explored the many specimens both displayed and available to touch. Some played more with the frog instruments or engaged in a variety of puzzles (including a frog puzzle!).

I think what’s great about this lesson is the fact that it can be done in just about any setting with objects. My recommendation for other educators without easily accessible museum spaces, but wishing to do a similar lesson would be to go sit outside or go to a local nature center or pond to connect with the concepts.

We made sure to say a quick goodbye to our frog skeletons before leaving Q?rius. Upon reflection, this would have been an excellent time to have the students take another look at the skeletons and have a brief discussion about what new information they had learned during the lesson. That would give them the opportunity to make connections and help to bring the visit full circle.

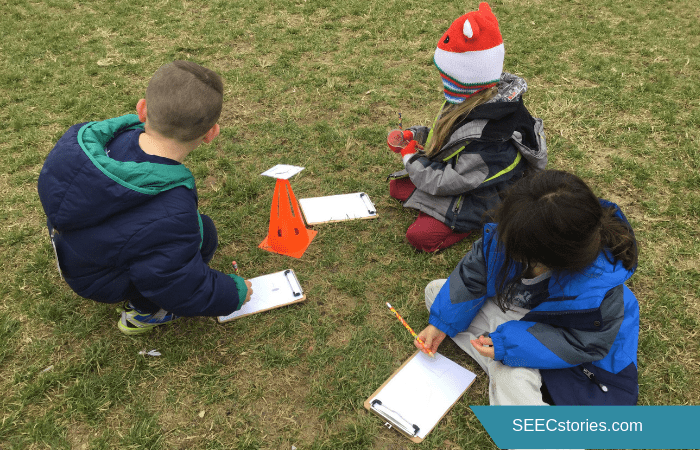

Later in the week, we continued the conversation by visiting the Moongate Garden to talk about the life cycle of frogs. Following our week on amphibians, we began to explore other animal classifications.

After exploring frogs the class learned about reptiles. For more animal ideas, visit our Amphibian, Birds, Reptile, and Ocean Pinterest boards.

The Journey

The Journey As a facilitator, I recognized my role in their discomfort and I felt like we needed to reconsider our approach – we were talking about inclusion after all. I had several questions:

As a facilitator, I recognized my role in their discomfort and I felt like we needed to reconsider our approach – we were talking about inclusion after all. I had several questions: In addition to this specific experience, we have been thinking about our entire menu of educator workshops through a DEAI lens. Some of the changes are small and obvious, and others are still in the “thinking” phase, but as I said….it’s a journey. Below is a list of ways we are thinking about DEAI in terms of our professional development options. These perspectives are with us as we rethink content and introduce new conversations to our educator programs.

In addition to this specific experience, we have been thinking about our entire menu of educator workshops through a DEAI lens. Some of the changes are small and obvious, and others are still in the “thinking” phase, but as I said….it’s a journey. Below is a list of ways we are thinking about DEAI in terms of our professional development options. These perspectives are with us as we rethink content and introduce new conversations to our educator programs. Considering how the museum community views families and young children and how we can help museum professionals understand that children are capable and should be respected. Helping museums think through how to make their spaces accessible to families, and how to support family learning.

Considering how the museum community views families and young children and how we can help museum professionals understand that children are capable and should be respected. Helping museums think through how to make their spaces accessible to families, and how to support family learning.

Meaning

Meaning Learning Extensions

Learning Extensions

At SEEC, our faculty uses an emergent curriculum, which means they follow the interests of the children to create units and lesson plans. They were able to connect the class’s interest in various topics including eggs, frogs, and bugs by exploring the life cycle of the butterfly.

At SEEC, our faculty uses an emergent curriculum, which means they follow the interests of the children to create units and lesson plans. They were able to connect the class’s interest in various topics including eggs, frogs, and bugs by exploring the life cycle of the butterfly.

The class’s museum visit began on their walk to the Freer|Sackler Galleries. They were able to weave this walk into their lesson as the class tried to spy butterflies.

The class’s museum visit began on their walk to the Freer|Sackler Galleries. They were able to weave this walk into their lesson as the class tried to spy butterflies. The class gathered around the Oscar de la Renta designs. The class looked closely at the textiles and discussed the colors and patterns that they saw.

The class gathered around the Oscar de la Renta designs. The class looked closely at the textiles and discussed the colors and patterns that they saw.

The class loved being outside and singing about butterfly wings. They were able to play with and further explore butterflies that they previously created.

The class loved being outside and singing about butterfly wings. They were able to play with and further explore butterflies that they previously created. On the walk back, the class went through the

On the walk back, the class went through the

Playing won’t give them the skills to be successful in life.

Playing won’t give them the skills to be successful in life.