For this week’s Teacher Feature we will highlight how our infant class investigated tea. Educators Brandi Gordon, J. Kelly, and Rebecca Morgan Parr took their class to the Smithsonian’s Enid A. Haupt Garden where they saw a tea plant in the Moongate. Afterwards they went back to our center where they made and drank tea. Below you will find images from the lesson and a reflection from the educators.

Preparation:

Prior to this lesson, the class had been learning about food and different things that people eat and drink. Inspired by the drinks that their parents, caregivers, and teachers had been consuming, they recently began exploring hot drinks including tea and coffee.

This tea lesson felt like a natural topic to explore after our class finished learning about fruits, vegetables, and other foods that grow from plants. We followed the interests of the children in our Duckling class who were interested in their teachers’ drinks. They children wanted to drink, touch, and taste our tea and coffee. In general, letting small children drink or handle hot beverages is not acceptable. We did not want to leave their interests ignored, so we decided to teach about them instead. We wanted to explore why some beverages feel hot and felt it was an excellent opportunity to reinforce language and safety ideas.

To learn more about tea, the class visited the Smithsonian’s Enid A. Haupt Garden where they were able to look at a tea plant.

For our objectives, we began by expanding upon the past units’ objectives. We had been teaching our Ducklings that many plants become the food that we eat, so visiting the tea plant was another way to do that. We also wanted more opportunities to explore our community, visit local shops, and see different parts of our school like the staff room, where we boiled the water to make tea. Another objective was to introduce our class to the idea of temperature. Lastly, we wanted to expose them to many kinds of tea as well as show them various beverages that exist in the world.

As educators, we had our own set of objectives for ourselves. We wanted to follow our class’s interest even if it was an unconventional topic. We wanted to weave the ideas of safety into a lesson. And we wanted to allow the children to embrace having sensory experiences. It was nice to remind ourselves that getting messy is ok and can be fun!

Lesson Implementation:

While looking at the tea plant, the educator Rebecca explained that people pick leaves from this plant to make tea.

Before the visit and on the way to the Moongate, we talked to the Ducklings about how we were going to see a tea plant. At the Moongate, we took the students out of the buggies and helped them into the circular marble seating next to the tea plant. We compared the real tea plant to the pretend tea plant and looked closely at the leaves.

Since plucking the tea leaves off the real tea plant would damage the plant, the educators brought their own pretend tea plant which was made by taping images of the tea plant to a cardboard box. To help the children experience plucking, they velcroed tea leaves to the box which the children were encouraged to pull off and put in a teapot.

The great thing about the pretend tea plant was that the children had the opportunity to pull off the leaves without hurting a live plant. After the Ducklings pulled the leaves off the box, we encouraged them to place them into tea bags which in turn they placed into our toy teapots. Then we poured pretend tea into their cups to drink. Many of the children loved pretending to drink out of the cups. As they pretended to make and drink the tea, we sang I’m a Little Tea Pot.

Some of children were more interested in playing with the water from the rain. They smacked their hands down on the marble seating to splash. We talked to the Ducklings about how we ingest plants for eating in many ways and that plants also go into tea. They had seen flowers throughout our gardening unit so the idea that some flowers can go in tea seemed to excite them.

The class returned to the center, to watch Kelly brew tea. Kelly talked about the different plants that can be used to make tea and poured hot water over tea leaves so the children could watch the steeping process.

We took our students into the kitchen area of the staff break room, where they began the beginnings of a circle time by sitting on the floor with their teachers. Kelly showed the class the electric kettle, tea bags, and the tea strainer. We gave out some tea bags to allow the students to explore. Some of the Ducklings started to rip the tea bags. We decided to encourage their exploration of the loose-leaf tea and asked questions like “What does that feel like?”

Children were encouraged to explore tea using their senses. They smelled tea, touched tea (and even pulled apart tea bags), and eventually tasted the tea.

We allowed free exploration. Some of the children enjoyed ripping the tea bags, some of them preferred chewing a strand of lavender, others placed dried rose petals into our tea strainer. We let the children stand up and sit down as they wished but made sure that they stayed within the confines of the small kitchen area so we could see everyone.

We tried to encourage our students to explore many kinds of sensory options. We also know that they are at an age when most things still go in their mouths for exploration and provide important details about the world around them. Tea is something they can learn about through all the senses–sight, sound, smell, touch and taste. They could see the tea, hear the water boil and steam, they could touch the dry and rehydrated tea leaves, smell the tea as it is brewing and finally taste it.

Reflection:

To conclude the lesson, the class had the opportunity to drink tea and as they drank, they engaged in conversation. Some children chose to clink cups as if they were cheering before drinking.Enter a caption

We followed up by this lesson by having the students “paint” with tea bags on a big sheet of paper. We continued to make different varieties of teas and visited the United States Botanical Garden to see different herbs that are used in tea (like mint.) Later in the afternoon, after everyone had woken up from their nap, we gave all of them a cup with the tea we made so they could try it as well as practice using open-face cups.

For other teachers trying this lesson, we recommend making sure whatever tea you use is decaffeinated and that the teas taste good to a child’s palate. Try to make sure you give enough time for the students to explore the objects and try to see how you can explore all the senses. Be flexible and open to mess– this is a great opportunity to allow each child to be an investigator, a scientist, a creative, and as always, their most curious self.

The Journey

The Journey As a facilitator, I recognized my role in their discomfort and I felt like we needed to reconsider our approach – we were talking about inclusion after all. I had several questions:

As a facilitator, I recognized my role in their discomfort and I felt like we needed to reconsider our approach – we were talking about inclusion after all. I had several questions: In addition to this specific experience, we have been thinking about our entire menu of educator workshops through a DEAI lens. Some of the changes are small and obvious, and others are still in the “thinking” phase, but as I said….it’s a journey. Below is a list of ways we are thinking about DEAI in terms of our professional development options. These perspectives are with us as we rethink content and introduce new conversations to our educator programs.

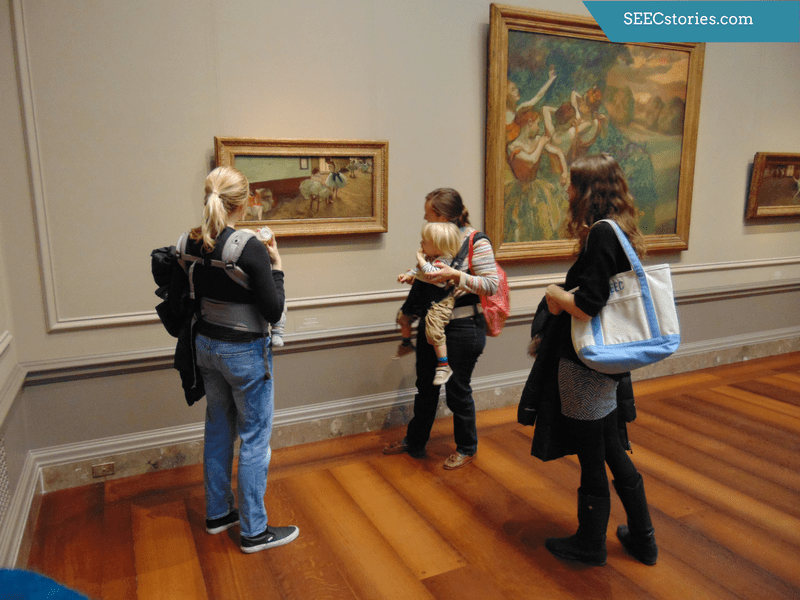

In addition to this specific experience, we have been thinking about our entire menu of educator workshops through a DEAI lens. Some of the changes are small and obvious, and others are still in the “thinking” phase, but as I said….it’s a journey. Below is a list of ways we are thinking about DEAI in terms of our professional development options. These perspectives are with us as we rethink content and introduce new conversations to our educator programs. Considering how the museum community views families and young children and how we can help museum professionals understand that children are capable and should be respected. Helping museums think through how to make their spaces accessible to families, and how to support family learning.

Considering how the museum community views families and young children and how we can help museum professionals understand that children are capable and should be respected. Helping museums think through how to make their spaces accessible to families, and how to support family learning.

Playing won’t give them the skills to be successful in life.

Playing won’t give them the skills to be successful in life. In a recent

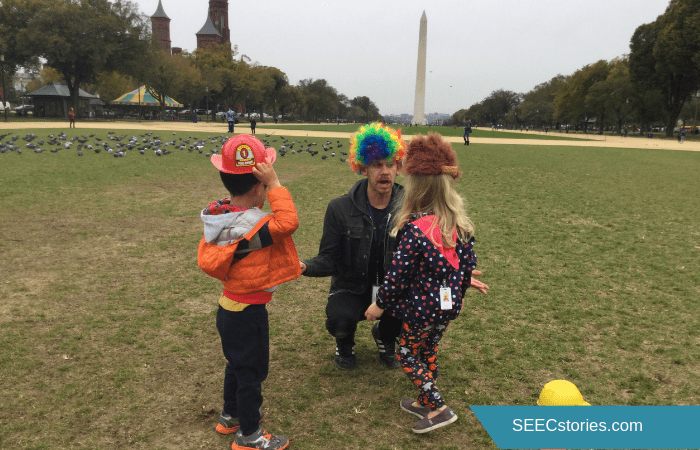

In a recent  The Secretary’s comments made me think more about the role museums can play in supporting a young child’s civic education. When I look specifically at SEEC, I see our school and programs as supporting a child’s understanding of democracy via museums in three ways. One of those ways, is asking them to understand the importance of objects from other cultures or historical periods. Many don’t see young children as capable of this type of perspective-taking, but with the right approach, young children can develop this type of understanding and empathy. One of the ways SEEC educators manage this is by taking what is familiar to children and applying it to the unfamiliar. Consider the collection of footwear on display at the Smithsonian Castle from the National Museum of the American Indian. The shoes, at first glance, may feel strange to a young child living in contemporary American society, but an educator can encourage a child to think beyond their own experiences by beginning with what they do know. A faculty member might inquire: “Why do we wear shoes? When do we wear certain types of shoes?, How do shoes help us?.” By applying these answers to the American Indian collection, children begin to see the many things we, humans, have in common. At the same time, a child are also able to acknowledge and celebrate the differences they observe. This type of lesson, especially if repeated, makes a lasting impression. We might be different, but those differences can be celebrated. It also underlines how we are part of one human family who shares many commonalities.

The Secretary’s comments made me think more about the role museums can play in supporting a young child’s civic education. When I look specifically at SEEC, I see our school and programs as supporting a child’s understanding of democracy via museums in three ways. One of those ways, is asking them to understand the importance of objects from other cultures or historical periods. Many don’t see young children as capable of this type of perspective-taking, but with the right approach, young children can develop this type of understanding and empathy. One of the ways SEEC educators manage this is by taking what is familiar to children and applying it to the unfamiliar. Consider the collection of footwear on display at the Smithsonian Castle from the National Museum of the American Indian. The shoes, at first glance, may feel strange to a young child living in contemporary American society, but an educator can encourage a child to think beyond their own experiences by beginning with what they do know. A faculty member might inquire: “Why do we wear shoes? When do we wear certain types of shoes?, How do shoes help us?.” By applying these answers to the American Indian collection, children begin to see the many things we, humans, have in common. At the same time, a child are also able to acknowledge and celebrate the differences they observe. This type of lesson, especially if repeated, makes a lasting impression. We might be different, but those differences can be celebrated. It also underlines how we are part of one human family who shares many commonalities. Secondly, young children who consistently spend time in museums can begin to understand and appreciate the role museums can play in learning, exploring, and questioning. During a recent conversation with a SEEC educator, he shared with me that in his Pre-K classroom children are routinely encouraged to ask questions and look for answers. He tell his class, that he, himself, doesn’t always have the answers and encourages them to seek answers via trusted resources. The children in this classroom have created a shortlist of “go to” places where they can get trusted answers. Of course, at the the top of this list is the museum. For our SEEC students who have spent much of their young lives in these institutions, they understand how museums provide not simply information, but concrete manifestations of this knowledge. Consider the toddler who is learning about colors and visits the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. His knowledge is expanded by exploring the artworks and seeing the many different hues of blue. Similarly, consider the kindergartner who is learning about Rosa Parks and after viewing her

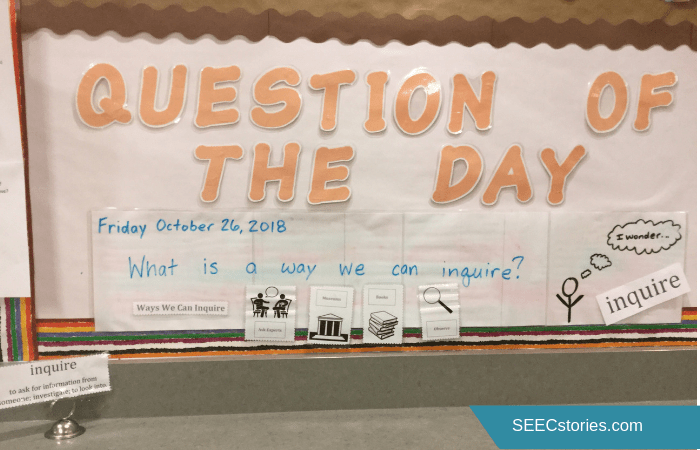

Secondly, young children who consistently spend time in museums can begin to understand and appreciate the role museums can play in learning, exploring, and questioning. During a recent conversation with a SEEC educator, he shared with me that in his Pre-K classroom children are routinely encouraged to ask questions and look for answers. He tell his class, that he, himself, doesn’t always have the answers and encourages them to seek answers via trusted resources. The children in this classroom have created a shortlist of “go to” places where they can get trusted answers. Of course, at the the top of this list is the museum. For our SEEC students who have spent much of their young lives in these institutions, they understand how museums provide not simply information, but concrete manifestations of this knowledge. Consider the toddler who is learning about colors and visits the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. His knowledge is expanded by exploring the artworks and seeing the many different hues of blue. Similarly, consider the kindergartner who is learning about Rosa Parks and after viewing her  Finally, the very nature of how we teach at SEEC (and I think you could say this is true for many museum and classroom educators) reaffirms trust in democratic discourse. SEEC lessons often begin with a question and are composed around a conversation. For example, we might pose a scientific question like, “Why do cars have wheels?” or something more abstract like, “How do you think the woman in the painting feels?.” By simply engaging young children in conversation we are helping them to develop socially and emotionally. By framing these conversations within a museum, we can also encourage children to see the institution as a place in which dialogue is part of the experience. Within that dialogue, educators can facilitate conversations that encourage children to listen to and respect the ideas of others – something which will hopefully cultivate a generation of leaders who can engage in conversations resulting in positive democratic change.

Finally, the very nature of how we teach at SEEC (and I think you could say this is true for many museum and classroom educators) reaffirms trust in democratic discourse. SEEC lessons often begin with a question and are composed around a conversation. For example, we might pose a scientific question like, “Why do cars have wheels?” or something more abstract like, “How do you think the woman in the painting feels?.” By simply engaging young children in conversation we are helping them to develop socially and emotionally. By framing these conversations within a museum, we can also encourage children to see the institution as a place in which dialogue is part of the experience. Within that dialogue, educators can facilitate conversations that encourage children to listen to and respect the ideas of others – something which will hopefully cultivate a generation of leaders who can engage in conversations resulting in positive democratic change. As early childhood educators, whether in the classroom or the museum, we have a unique opportunity to frame the museum as a place where children can acquire knowledge throughout their life. Museum education is so much more than learning a new fact. It is a place where people of all ages can apply new information in a way that helps them value different perspectives and understand the ideas of others. While SEEC is uniquely situated to achieve this as a school on the Smithsonian campus, all schools and museums can support these democratic values. Classroom faculty can engage in conversations at their schools utilizing museum objects as a focal point via online resources. Museum educators can cultivate educational experiences that are friendly to all families and and frame developmentally appropriate experiences that support young children as capable learners. If we can support learning in this open-ended way, museums can and will remains stalwarts of democracy.

As early childhood educators, whether in the classroom or the museum, we have a unique opportunity to frame the museum as a place where children can acquire knowledge throughout their life. Museum education is so much more than learning a new fact. It is a place where people of all ages can apply new information in a way that helps them value different perspectives and understand the ideas of others. While SEEC is uniquely situated to achieve this as a school on the Smithsonian campus, all schools and museums can support these democratic values. Classroom faculty can engage in conversations at their schools utilizing museum objects as a focal point via online resources. Museum educators can cultivate educational experiences that are friendly to all families and and frame developmentally appropriate experiences that support young children as capable learners. If we can support learning in this open-ended way, museums can and will remains stalwarts of democracy.