Introduction

Earlier this year, educators across SEEC’s vibrant community came together for an all-class meeting led by our Office of Engagement and Administrative Team. With representation from every classroom serving children from 2 months to 4 years, this gathering was an opportunity to reflect, share, and envision the future of our learning environments.

The heart of the presentation focused on how classroom environments at SEEC should be more than just spaces—they should be reflections of what’s happening in the life of each class. They should be intentional, curated, and consistent across our community. As a lab school that integrates museums, community connections, play, and object-based learning, our environment serves not only as a backdrop, but also as an active participant in the learning process.

The display boards in the Art Studio about the children’s exploration of Pacita’s Painted Bridge; the top left board discusses the inspiration from the art with descriptive posters, the top right board features a “Talking with Art” theme with children’s art and comments, the bottom board showcases multiple photos and descriptions of children engaged in the process of creating their pieces.

Documentation is …

“An effective piece of documentation tells the story and the purpose of an event, experience, or development. It is a product that draws others into the experience—evidence or artifacts that describe a situation, tell a story, and help the viewer to understand the purpose of the action”

– NAEYC

Art display featuring a colorful collage with images, patterns, and cellophane fish, all pinned on a wall. It also features photographs of the children creating the fish, an image of Untitled by Simon George Mpata and a description plaque of the children’s exploration.

Guidelines for Curated Spaces

The administrative team outlined several key guidelines for building and sustaining rich classroom environments. One major takeaway was the idea of keeping displays fresh and relevant by changing them out monthly in alignment with each class’s unit of learning. Educators were encouraged to use real photos whenever possible, and to be mindful of how someone without any context—a new family, a visitor, or even a child—might engage with the documentation they encounter.

Importantly, the team challenged educators to think beyond the bulletin board. Documentation should be thoughtfully showcased, using the full range of space within the classroom to reflect learning, discovery, and growth. Typed descriptions should support the visuals, offering clear, intentional narratives about what is happening and why it matters.

A display featuring multiple photos of children in our Threes class engaging in the process of creating lanterns, and a text panel describing their exploration of lights during the holidays, complemented by a display of their lanterns.

Showcasing the Extraordinary

Another theme of the presentation was recognizing and intentionally showcasing the extraordinary work that is happening every day in our classrooms. Documentation is a tool for storytelling—and those stories should be shared with our caregivers, our peers, and the children themselves. It fosters connection, supports classroom community, and builds trust with families.

We revisited an important question: Who is documentation for? The answer was multifaceted. It’s for children, who deserve to see their learning reflected back at them. It’s for caregivers, who want to understand and engage with their child’s experience. It’s for fellow educators, directors, and even for each of us as individual educators—a way to reflect on and grow in our own practice. It’s also a window for new families into the values and rhythms of SEEC classrooms.

Left: An outdoor class exhibit with a child and their caregiver viewing paper artworks.

Right: A caregiver reading a description of their child’s class art display while two children and two educators engage in play and story time.

Engaging Children Through Environment

The team emphasized that placement matters. Documentation intended for children should be placed low enough for them to engage with it—yes, even to touch it. When we introduce materials thoughtfully and set expectations, children can interact with their learning environment in respectful and meaningful ways.

We also explored how the environment itself can shape classroom behavior. A carefully arranged, engaging, and responsive space can reduce challenges and support deeper exploration. Our surroundings can either hinder or enhance the work we do—and we have the power to use them intentionally.

Wall display at child level featuring one of our Twos’ class artworks and a descriptive plaque, in a classroom setting.

From Discussion to Action

The presentation concluded with an open dialogue. Educators discussed practical concerns—how to manage time constraints, where to print documentation, and how to embrace the idea that children will interact physically with the materials on display.

In the five months since, educators across SEEC have taken this guidance to heart. Classrooms are now filled with purposeful documentation that highlights the daily wonders unfolding in our community. From toddler rooms to preschool spaces, there’s a renewed commitment to documenting learning not just consistently, but meaningfully.

As we look ahead, our goal is to continue growing in this work—pushing ourselves to create environments that don’t just display learning but deepen and celebrate it.

Top: A display in our older infant class featuring the work of Alma Thomas alongside the children’s artwork. Bottom: Abstract paintings and textured art pieces by one of our toddler classes, and a central portrait of Piet Mondrian with a description of the children’s exploration of his art.

The class headed straight to the National Museum of Natural History to start exploring their topic! They first stopped in the Icelandic photo exhibition to find some cold environments. These two are pretending to shiver from being in the ice landscape behind them.

The class headed straight to the National Museum of Natural History to start exploring their topic! They first stopped in the Icelandic photo exhibition to find some cold environments. These two are pretending to shiver from being in the ice landscape behind them. Their next stop was animals of North America in the Mammal Hall.

Their next stop was animals of North America in the Mammal Hall. Melinda brought along photos of winter clothing and animals for the children to hold in the gallery,

Melinda brought along photos of winter clothing and animals for the children to hold in the gallery, She also brought along animal fur that corresponded to the animals in the exhibits. She explained that animals have different ways to keep themselves warm and safe in the winter.

She also brought along animal fur that corresponded to the animals in the exhibits. She explained that animals have different ways to keep themselves warm and safe in the winter. Melinda then explained that people don’t have fur to keep them warm so we have to get dressed for the winter instead. She got dressed in winter attire and proceeded to sing a winter clothing version of “head, shoulders, knees, and toes” (lyrics above).

Melinda then explained that people don’t have fur to keep them warm so we have to get dressed for the winter instead. She got dressed in winter attire and proceeded to sing a winter clothing version of “head, shoulders, knees, and toes” (lyrics above).  The children then took turns trying on different winter clothing items. Melinda included some clothing that mimicked fur or were made from the wool/fur of animals so that the children could feel how warm these animals are kept by their skin.

The children then took turns trying on different winter clothing items. Melinda included some clothing that mimicked fur or were made from the wool/fur of animals so that the children could feel how warm these animals are kept by their skin.

One little girl brought a stuffed wolf to the table because she had matched the fur in the bowl to the animal.

One little girl brought a stuffed wolf to the table because she had matched the fur in the bowl to the animal. This lesson inspired lots of curiosity and provided many different interactions between the children and teachers!

This lesson inspired lots of curiosity and provided many different interactions between the children and teachers! Our inaugural Object of the Month is actually not so much an object, but a gallery. The Rocks Gallery in the National Museum of Natural History is tucked at the back of the

Our inaugural Object of the Month is actually not so much an object, but a gallery. The Rocks Gallery in the National Museum of Natural History is tucked at the back of the

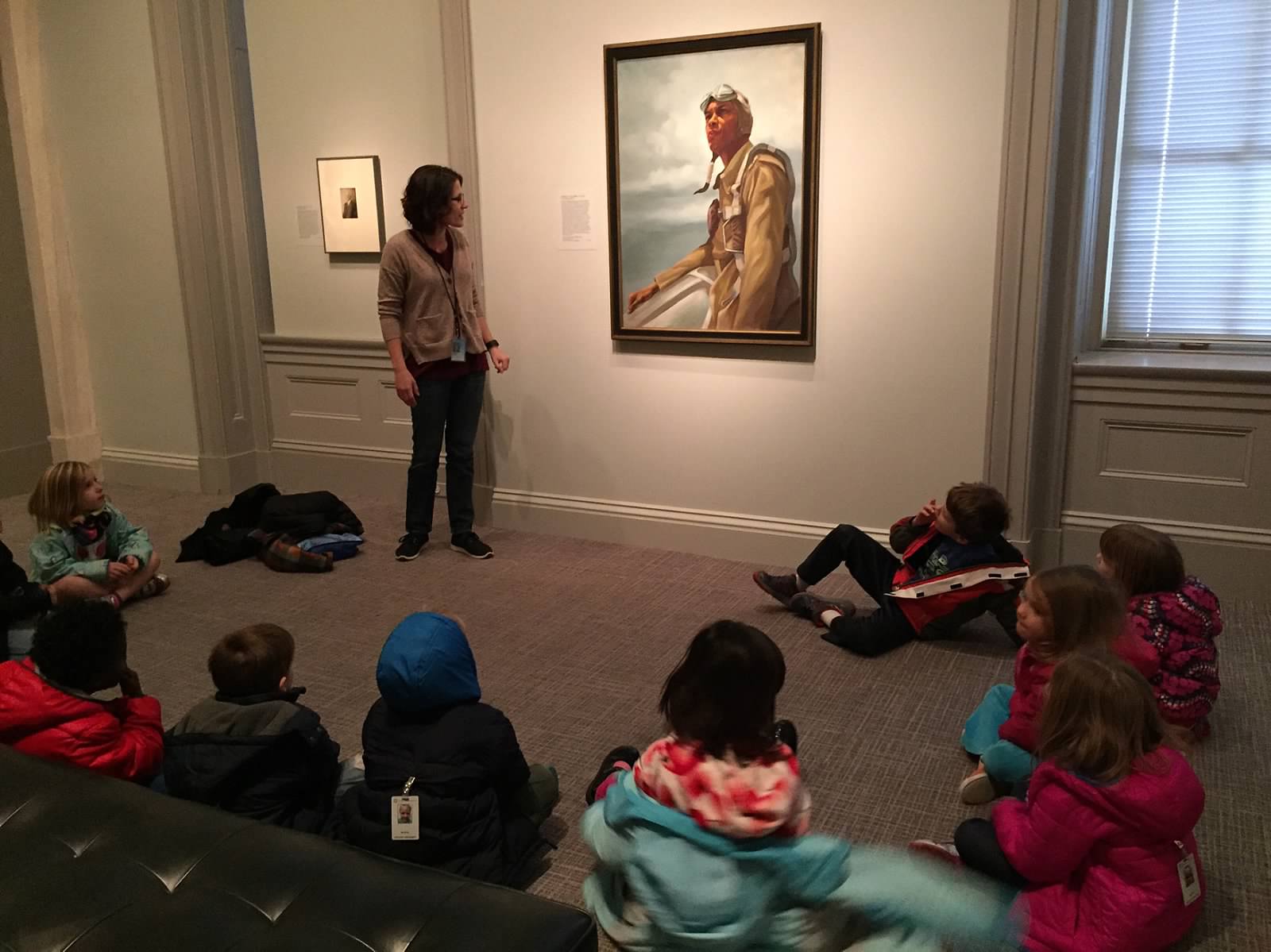

As the last part of the object lesson, I laid out several objects and asked them to work together to recreate the painting. They needed no instruction, but went right to work, collaborating until the composition was complete. Was it exactly like the painting, no, but they had used these tools to create their OWN composition. They were quite proud and were completely engaged in the activity. I saw them looking back at the painting, rearranging objects and making their own decisions.

As the last part of the object lesson, I laid out several objects and asked them to work together to recreate the painting. They needed no instruction, but went right to work, collaborating until the composition was complete. Was it exactly like the painting, no, but they had used these tools to create their OWN composition. They were quite proud and were completely engaged in the activity. I saw them looking back at the painting, rearranging objects and making their own decisions.

Meg had the group gather at the front of the exhibit. She passed out different animals found in Africa and invited the children to let her know when they saw the same animal in her book: Rumble in the Jungle by Giles Andeae.

Meg had the group gather at the front of the exhibit. She passed out different animals found in Africa and invited the children to let her know when they saw the same animal in her book: Rumble in the Jungle by Giles Andeae.