In a recent article Smithsonian Secretary Skorton posited that museums can help people regain trust in “traditional democratic institutions”. His argument centered around a study indicating that many Americans have lost faith in the institutions that are the foundation of our democratic system. He spoke to the fact that not just Americans, but citizens across the globe seem to be losing trust in their own societies and pondered how a democracy can function without the trust of its citizens. Secretary Skorton sees museums and libraries, not only as institutions that provide reliable and objective information, but also as places where questions can be posed, dialogues can be had, and a variety of perspectives can be explored. As leader of the Smithsonian, moreover, he sees museums as places where communities can come together to better understand themselves and the world around them.

In a recent article Smithsonian Secretary Skorton posited that museums can help people regain trust in “traditional democratic institutions”. His argument centered around a study indicating that many Americans have lost faith in the institutions that are the foundation of our democratic system. He spoke to the fact that not just Americans, but citizens across the globe seem to be losing trust in their own societies and pondered how a democracy can function without the trust of its citizens. Secretary Skorton sees museums and libraries, not only as institutions that provide reliable and objective information, but also as places where questions can be posed, dialogues can be had, and a variety of perspectives can be explored. As leader of the Smithsonian, moreover, he sees museums as places where communities can come together to better understand themselves and the world around them.

As an organization, SEEC, also sees museums, libraries, and the larger community as sources for information, discussion, and reflection. We were particularly excited when in the same article, Skorton noted the role of educators:

I have seen how our museums and centres engage visitors and transform the way they see the world—especially our youngest visitors, who light up with the joy of new discovery. Through our education programs, we reach millions of national and international students, often using objects from our collections to demonstrate experiences and viewpoints that differ from what they might have encountered. By revealing history through the lens of diverse perspectives, museums humanize other cultures and contextualize present-day events and people.

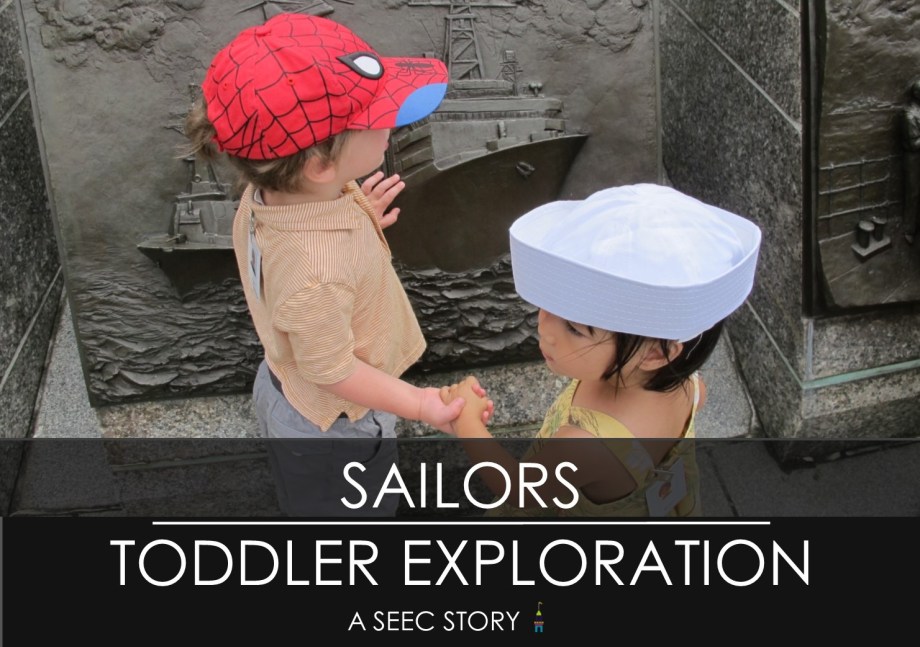

The Secretary’s comments made me think more about the role museums can play in supporting a young child’s civic education. When I look specifically at SEEC, I see our school and programs as supporting a child’s understanding of democracy via museums in three ways. One of those ways, is asking them to understand the importance of objects from other cultures or historical periods. Many don’t see young children as capable of this type of perspective-taking, but with the right approach, young children can develop this type of understanding and empathy. One of the ways SEEC educators manage this is by taking what is familiar to children and applying it to the unfamiliar. Consider the collection of footwear on display at the Smithsonian Castle from the National Museum of the American Indian. The shoes, at first glance, may feel strange to a young child living in contemporary American society, but an educator can encourage a child to think beyond their own experiences by beginning with what they do know. A faculty member might inquire: “Why do we wear shoes? When do we wear certain types of shoes?, How do shoes help us?.” By applying these answers to the American Indian collection, children begin to see the many things we, humans, have in common. At the same time, a child are also able to acknowledge and celebrate the differences they observe. This type of lesson, especially if repeated, makes a lasting impression. We might be different, but those differences can be celebrated. It also underlines how we are part of one human family who shares many commonalities.

The Secretary’s comments made me think more about the role museums can play in supporting a young child’s civic education. When I look specifically at SEEC, I see our school and programs as supporting a child’s understanding of democracy via museums in three ways. One of those ways, is asking them to understand the importance of objects from other cultures or historical periods. Many don’t see young children as capable of this type of perspective-taking, but with the right approach, young children can develop this type of understanding and empathy. One of the ways SEEC educators manage this is by taking what is familiar to children and applying it to the unfamiliar. Consider the collection of footwear on display at the Smithsonian Castle from the National Museum of the American Indian. The shoes, at first glance, may feel strange to a young child living in contemporary American society, but an educator can encourage a child to think beyond their own experiences by beginning with what they do know. A faculty member might inquire: “Why do we wear shoes? When do we wear certain types of shoes?, How do shoes help us?.” By applying these answers to the American Indian collection, children begin to see the many things we, humans, have in common. At the same time, a child are also able to acknowledge and celebrate the differences they observe. This type of lesson, especially if repeated, makes a lasting impression. We might be different, but those differences can be celebrated. It also underlines how we are part of one human family who shares many commonalities.

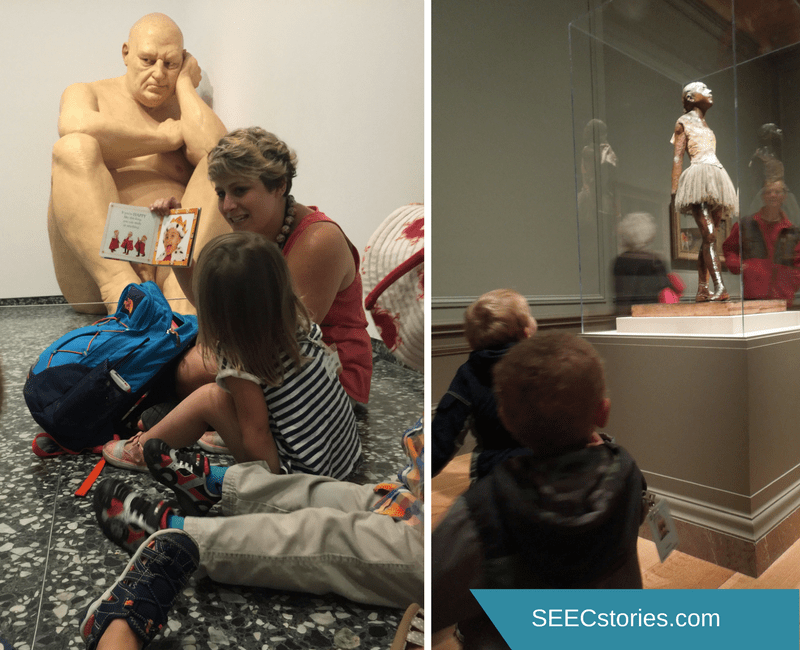

Secondly, young children who consistently spend time in museums can begin to understand and appreciate the role museums can play in learning, exploring, and questioning. During a recent conversation with a SEEC educator, he shared with me that in his Pre-K classroom children are routinely encouraged to ask questions and look for answers. He tell his class, that he, himself, doesn’t always have the answers and encourages them to seek answers via trusted resources. The children in this classroom have created a shortlist of “go to” places where they can get trusted answers. Of course, at the the top of this list is the museum. For our SEEC students who have spent much of their young lives in these institutions, they understand how museums provide not simply information, but concrete manifestations of this knowledge. Consider the toddler who is learning about colors and visits the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. His knowledge is expanded by exploring the artworks and seeing the many different hues of blue. Similarly, consider the kindergartner who is learning about Rosa Parks and after viewing her portrait by Marshall D. Rumbaugh at the National Portrait Gallery. Through age-appropriate conversation, she can gain deeper insight into Parks’ role in the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Both children are learning that the museum is a place where they can turn to for both factual information and for viewpoints other than their own.

Secondly, young children who consistently spend time in museums can begin to understand and appreciate the role museums can play in learning, exploring, and questioning. During a recent conversation with a SEEC educator, he shared with me that in his Pre-K classroom children are routinely encouraged to ask questions and look for answers. He tell his class, that he, himself, doesn’t always have the answers and encourages them to seek answers via trusted resources. The children in this classroom have created a shortlist of “go to” places where they can get trusted answers. Of course, at the the top of this list is the museum. For our SEEC students who have spent much of their young lives in these institutions, they understand how museums provide not simply information, but concrete manifestations of this knowledge. Consider the toddler who is learning about colors and visits the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. His knowledge is expanded by exploring the artworks and seeing the many different hues of blue. Similarly, consider the kindergartner who is learning about Rosa Parks and after viewing her portrait by Marshall D. Rumbaugh at the National Portrait Gallery. Through age-appropriate conversation, she can gain deeper insight into Parks’ role in the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Both children are learning that the museum is a place where they can turn to for both factual information and for viewpoints other than their own.

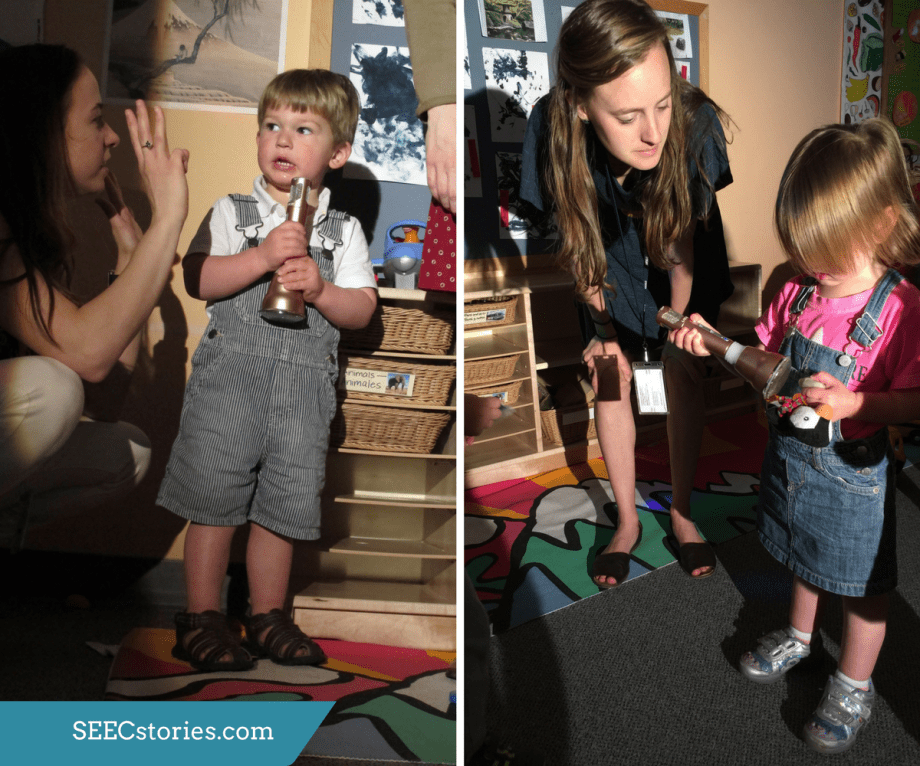

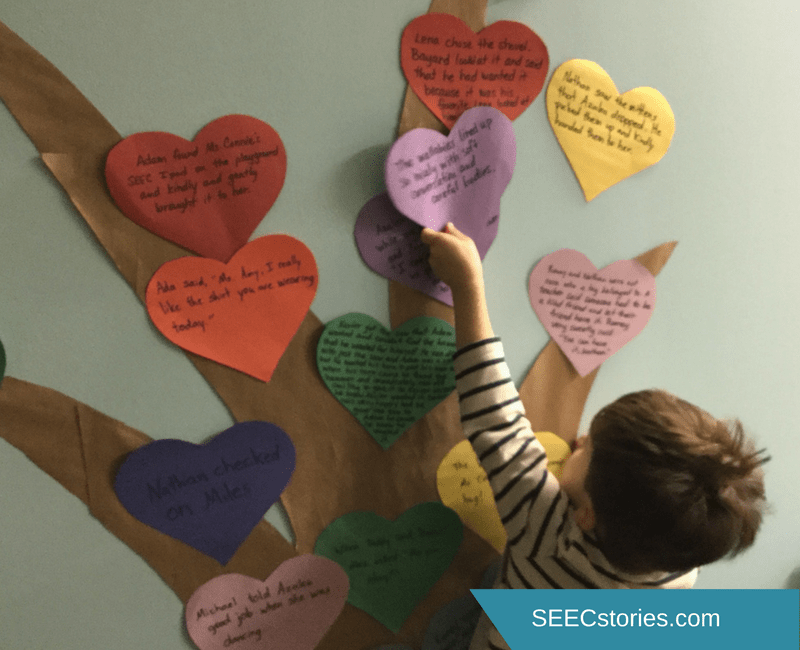

Finally, the very nature of how we teach at SEEC (and I think you could say this is true for many museum and classroom educators) reaffirms trust in democratic discourse. SEEC lessons often begin with a question and are composed around a conversation. For example, we might pose a scientific question like, “Why do cars have wheels?” or something more abstract like, “How do you think the woman in the painting feels?.” By simply engaging young children in conversation we are helping them to develop socially and emotionally. By framing these conversations within a museum, we can also encourage children to see the institution as a place in which dialogue is part of the experience. Within that dialogue, educators can facilitate conversations that encourage children to listen to and respect the ideas of others – something which will hopefully cultivate a generation of leaders who can engage in conversations resulting in positive democratic change.

Finally, the very nature of how we teach at SEEC (and I think you could say this is true for many museum and classroom educators) reaffirms trust in democratic discourse. SEEC lessons often begin with a question and are composed around a conversation. For example, we might pose a scientific question like, “Why do cars have wheels?” or something more abstract like, “How do you think the woman in the painting feels?.” By simply engaging young children in conversation we are helping them to develop socially and emotionally. By framing these conversations within a museum, we can also encourage children to see the institution as a place in which dialogue is part of the experience. Within that dialogue, educators can facilitate conversations that encourage children to listen to and respect the ideas of others – something which will hopefully cultivate a generation of leaders who can engage in conversations resulting in positive democratic change.

As early childhood educators, whether in the classroom or the museum, we have a unique opportunity to frame the museum as a place where children can acquire knowledge throughout their life. Museum education is so much more than learning a new fact. It is a place where people of all ages can apply new information in a way that helps them value different perspectives and understand the ideas of others. While SEEC is uniquely situated to achieve this as a school on the Smithsonian campus, all schools and museums can support these democratic values. Classroom faculty can engage in conversations at their schools utilizing museum objects as a focal point via online resources. Museum educators can cultivate educational experiences that are friendly to all families and and frame developmentally appropriate experiences that support young children as capable learners. If we can support learning in this open-ended way, museums can and will remains stalwarts of democracy.

As early childhood educators, whether in the classroom or the museum, we have a unique opportunity to frame the museum as a place where children can acquire knowledge throughout their life. Museum education is so much more than learning a new fact. It is a place where people of all ages can apply new information in a way that helps them value different perspectives and understand the ideas of others. While SEEC is uniquely situated to achieve this as a school on the Smithsonian campus, all schools and museums can support these democratic values. Classroom faculty can engage in conversations at their schools utilizing museum objects as a focal point via online resources. Museum educators can cultivate educational experiences that are friendly to all families and and frame developmentally appropriate experiences that support young children as capable learners. If we can support learning in this open-ended way, museums can and will remains stalwarts of democracy.

References

Skorton, David J. “How Do We Restore Trust in Our Democracies?” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 12 Mar. 2018, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-do-we-restore-trust-our-democracies-museums-can-be-starting-point-180968448/#FsSTi0ZDsl6qSVV0.99.

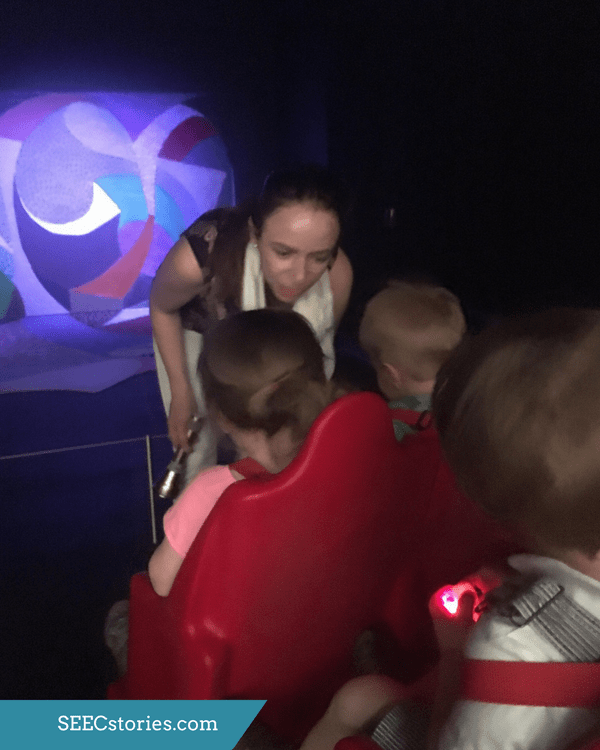

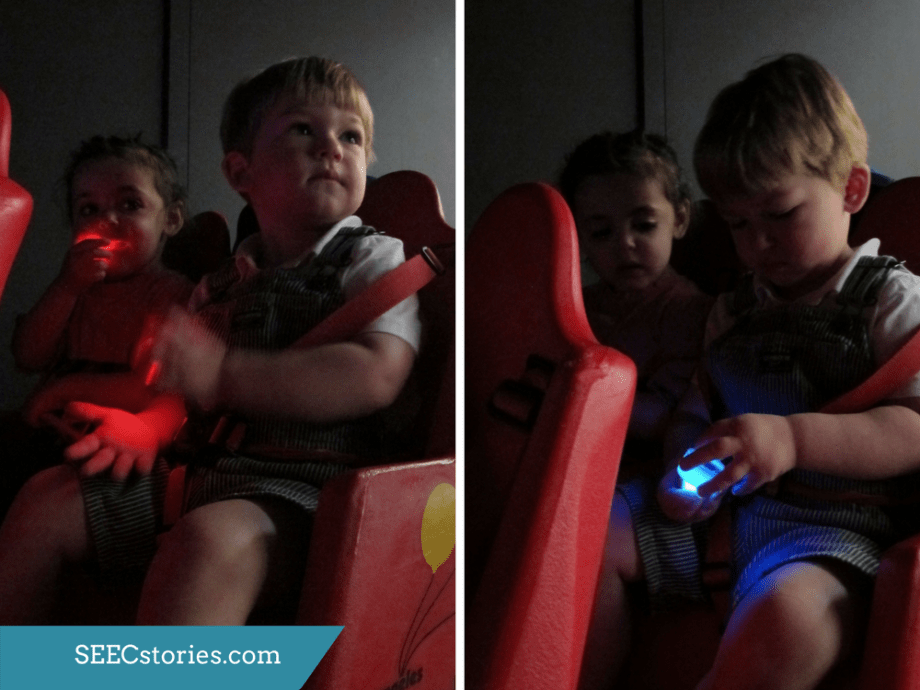

Light was another topic that the teachers were hoping to explore with their class since karaoke performances often involve a light show. As part of the instillation of Snail Space color changing lights are projected onto the two canvas’ and floor space design. In addition to experiencing the light that is part of the performance of Snail Space, the teachers brought battery powered tea lights to allow the children to explore and manipulate their own light.

Light was another topic that the teachers were hoping to explore with their class since karaoke performances often involve a light show. As part of the instillation of Snail Space color changing lights are projected onto the two canvas’ and floor space design. In addition to experiencing the light that is part of the performance of Snail Space, the teachers brought battery powered tea lights to allow the children to explore and manipulate their own light.